Despite the risk of stranded assets and the disastrous effects of runaway climate change, investors have largely ignored calls to form exit strategies from their fossil fuel investments and stand accused of “playing both sides” in the hope of continuing ‘business as usual’, while conversely promoting their sustainability credentials.

A recent update to the Investing in Climate Chaos webpage, published by non-profit environmental organisation Urgewald, showed analysis uncovering $4.3trn of investments in fossil fuel companies from institutional investors. These included holdings in companies featured in the Global Coal Exit List (GCEL) and Global Oil & Gas Exit List (GOGEL), Urgewald found. Further, in May 2024, some 5,260 institutional investors were still holding bonds and shares in coal companies, adding up to £1.2trn. Over 95% of companies on the GCEL have failed to set a coal exit date, and 40% are still planning to develop new coal assets.

Likewise, 7,245 institutional investors were still invested in an expanding oil and gas industry, with a total value of $3.8trn. Of the companies featured on the GOGEL, 96% are still exploring and developing new oil and gas reserves, while the industry as a whole has increased its annual capital expenditure on oil and gas exploration by more than 30% since 2021.

“In 2024, the year of climate finance after countries unanimously agreed to phase down the use of fossil fuels at COP28, it is astounding that institutional investors hold $4trn worth of shares and bonds of companies that are deliberately expanding their coal, oil and gas production,” said for Katrin Ganswindt, head of financial research at Urgewald.

However, while such big investments in oil and gas companies were not so much of a surprise, given the huge profit the industry is making currently, Ganswindt said it was harder to justify the large investment in coal. Further, it was “especially surprising” to see European companies still strongly invested in “the world’s biggest climate killer”.

“For some, it is easier to continue business as usual, to stay in the game. Especially when there is insufficient pressure from regulators or shareholders,” she continued.

Stranded asset risk

Given the positive noise around energy transition – with the cost of renewable energy generation decreasing rapidly – it seems logical to conclude the demand for fossil fuels such as coal, oil and gas will decrease over time. This increases the risk of stranded assets: assets that have suffered from unanticipated or premature write-downs, devaluations or conversion to liabilities, according to Mike Coffin, head of oil, gas and mining research at the Carbon Tracker initiative.

For the fossil fuel industry, there are two separate kinds of stranded assets. Infrastructure with a fixed capacity, such as refineries and power generation assets, will increasingly find themselves underutilised and their margins decreasing. At some point, these assets will have to shut down early, as the case to continue to invest starts to get more difficult. On the other hand, assets such as an oil or gas field will have to go through a period of natural decline over time. Historically, companies at that stage look to reinvest in new projects to keep production going but, given the gradual transition to a net zero emissions economy, the emphasis has shifted to avoiding investing in new projects and managing existing ones over the next 10 to 20 years until they stop production.

Coffin added no one credible is saying we must stop using oil and gas tomorrow, but “it’s just about avoiding new explorations and managing the existing decline”.

So, what’s an investor’s role here?

“We need to separate the investor into two communities: one, those that have a mandate to take climate into account in their investments or invest from a ‘do no harm’ perspective, and two, those that invest purely from a financial perspective. With that latter group, the problem is, their role is to manage and protect the value of their investments for their clients, so they can’t afford to allow the companies in which they invest to squander capital on projects that are not going to be value-additive – including in the fossil fuel industry,” asserts Coffin.

“The key to that is working with and challenging companies over their forecasts for product demand and pricing. Fund managers should also make sure companies are disclosing the information they have on those issues, ensuring those figures are consistent with the pace of transition that companies are articulating.”

Radio silence on exit strategies

However, when PA Future reached out for input on this article from the world of investment management, no firms were willing to comment, other than that the premise of sunsetting oil and gas investments to avoid the risk of stranded assets was “a forward-thinking hypothetical” – according to one group off the record.

For Mark Campanale, founder and director of the Carbon Tracker initiative, this was of no great surprise.

“The oil and gas industry has underperformed the S&P500 for the last decade, but you get a short-term blip like we’ve seen resulting from the war in Ukraine, and suddenly everyone’s saying ‘we need more oil and gas in our portfolios’. But the industry is an imperfect market – we have OPEC, which is basically a cartel at this point – with very few sellers and multiple buyers, and the sellers can dictate the price. But now, we have new entrants to the market, and the renewables sector – batteries, solar, wind – has become the cheapest form of energy around the world. These cartels will eventually be broken up because of the competition driving prices down, and that worries investors who’ve banked on the high dividends they’re currently receiving from these oil and gas companies. As demand falls, investors will be forced to rethink and pull away.”

Coffin agreed and added similar positive noise about the multiples of investing in fossil fuels being low is “a game of musical chairs”.

“Multiples change over time, and, to the comment on exit strategies being a ‘forward-thinking hypothetical’, markets are forward-looking, and it’s an asset manager’s job to be forward-looking too because, ultimately, if they’re not, they’re likely to get caught out by asset price changes.

“Additionally, there are a number of myths about how renewables won’t give the same returns that oil and gas have historically been able to give investors. No one’s saying investors must shed their oil and gas stocks and go into renewables; investors can go into almost anything else. Actually, the reduction in supernormal profits probably means that the energy sector, as a weighting within a portfolio, should shrink. The point is that future oil and gas won’t deliver the same returns as historic oil and gas has done. So, it’s about dispelling those myths propagated from within the fossil fuels industry itself.”

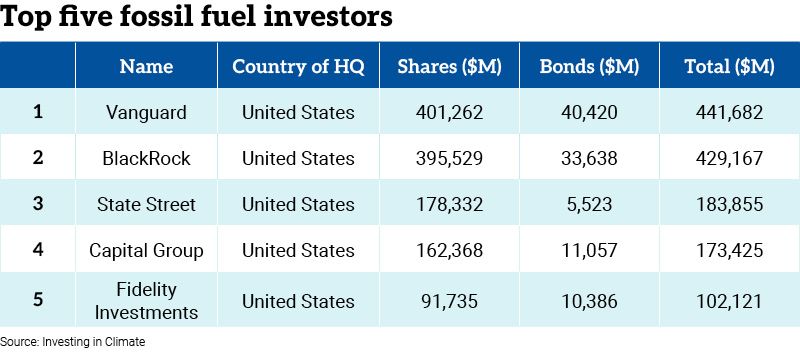

Given that many passive funds invest in fossil fuels – for example, Vanguard, one of the largest global passive investors, came top of a list of firms invested in fossil fuels with $413bn in coal, oil and gas holdings – could investors hide behind this to present a narrative that they have no control over their investments?

“That would be a massive cop-out”, Coffin said. “As well as having the ability to choose which index a passive fund follows, a passive fund can also have a sustainable mandate with a sustainable benchmark. Additionally, passive investors can still vote actively, holding companies accountable for transitioning to a net zero economic model.

“Given the rise in passive funds over the last decade, maybe there’s an argument to be had over whether passive funds weighted with a high-energy bias should be returned to active management,” posed Coffin.

Engagement vs divestment: What are the solutions?

Much of the conversation around investing in fossil fuel companies, meanwhile, boils down to whether to ‘divest’ and place those companies within a fund’s exclusionary practices, or to ‘engage’ with those companies to support them on their decarbonisation journey, and therefore ensuring those assets do not fall into the hands of another investment firm that may not have a robust engagement strategy on sustainability.

For Ganswindt, the recent backlash against sustainable investment and ESG – a “right-wing surge”, as she described it – downplayed climate concerns and was an attempt to block the transition from taking place. That affects investment decisions, she asserted.

“Also, investors like to preach engagement will solve the climate crisis and they need to stay invested to make a difference. However, engagement alone does not change anything. Pairing engagement with divestment – now that is really effective. The threat of divestment must figure prominently in any serious engagement to secure real results.”

Despite the heavy criticism, results from Urgewald’s study point to some positive signals from some investors. Allianz, for example, was considered to have a good policy on coal but failed to apply it to its subsidiaries AGI and PIMCO. Several French asset managers and owners, such as Ircantec, La Banque Postal and Credit Mutuel, were also found to have good oil and gas policies, with French regulators making efforts to improve climate policies in France’s financial sector.

Campanale, however, said the divestment and/or engagement argument is a moot point: “Investors buy and sell every day. When they sell a share, they don’t say ‘I’ve divested that company’, they’ve just decided to sell because they don’t feel the investment makes sense anymore. What we’ve got right now is a bunch of investors who think the fossil fuel system is ending, and they’re simply selling their shares because they don’t believe in the future viability of these companies. It isn’t they ‘divested’, they just sell them because it makes common sense.

“On engagement, let’s take the Industrial Revolution as an example and the switch from canals to railroads. Investors didn’t ‘engage’ with the canal companies to make canals more efficient. They just switched their investments to the railways because it was better, cheaper and more efficient. Likewise, when cars became a thing. So, this ‘divestment or engagement’ idea is absolute nonsense.”

For funds that do not have a sustainability mandate, then, how can clients instruct investment managers to incorporate an exit strategy in their fossil fuel investments? Campanale argued if a client is picking a fund manager that votes client shares against the energy transition, and doesn’t have a properly resourced stewardship team, “they’re probably not the right fund manager for you”.

“You also have to find out, when it comes to quantifying risk, whether a fund manager is using a business-as-usual scenario, assuming all demand stays high. If that’s the case, then they’ll build a financial model based on that, including a net present value that incorporates a terminal value.

“The problem is there is no positive terminal value for a coal-fired power station – who’s going to want to buy it these days? And who’s going to want to buy an oil refinery when people aren’t using so much oil? When fund managers decide to operate this way, that’s a choice, that’s a decision they’ve made. So, for a client interested in sustainable investment, they need to find a fund manager who assumes write-downs, assumes a high cost of capital and assumes that we’re not going to need so much capacity.”

Given the holistic nature of energy transition and the drive to a net-zero global economy, the risks involved with investing in the fossil fuel industry are beginning to snowball. And yet, the silence from investors on whether they’ve discussed an exit strategy from these investments in the medium- to long-term speaks volumes. Perhaps market and geopolitical volatility has forced asset managers’ heads into the sand, or clouded their ability to be more forward-thinking. But the need for clarity in this regard is paramount – and if investors don’t know which way to go, its up to clients to light the way.