Public companies are emitting greenhouse gases at a rate that will roughly double the 1.5°C preindustrial average temperature rise outlined in the Paris Agreement, according to MSCI.

The ratings and research firm on Tuesday put out a report finding that if companies stay on their current course, global temperatures will increase by 2.9°C, with businesses on track to burn through their carbon emissions budgets associated with a 1.5°C rise by 2027.

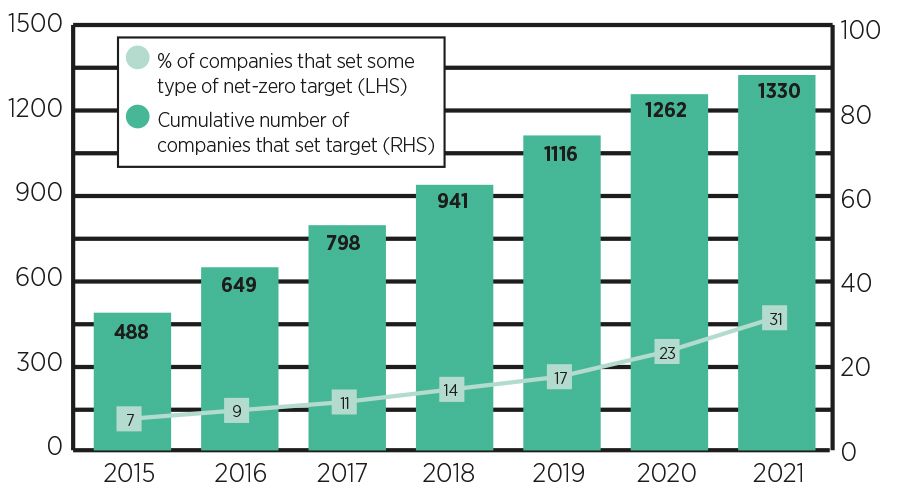

However, that projection is down by 0.1°C since a similar report from MSCI in October, as many companies have adopted emissions-reduction targets.

“The slowdown in the growth of corporate emissions means the time for listed companies to limit warming to 1.5°C has lengthened by three months since we projected last October,” the firm said in its new report.

“We now estimate that listed companies will burn through their share of the global carbon budget for keeping temperature rise below 1.5°C by February 2027, based on their emissions as of May 31, 2022.”

Companies setting decarbonization and net-zero targets

Companies have been taking more action around climate risk in response to pressure from shareholders and regulators – and some businesses have become aware of the consequences they will face in a world with higher temperatures.

MSCI reviewed data from nearly 9,200 public companies that are in its All Country World Investable Market Index, which includes small, medium and large businesses.

Among those companies, 46% have goals set with a 2°C average global temperature rise, which is “at the high end of the Paris Agreement goal,” MSCI’s report noted.

By comparison, 11% of companies have goals in line with a 1.5°C temperature rise, “the threshold above which scientists say the risk of catastrophic climate hazards increases significantly,” up from 10% of companies that had that goal as of October, according to the report.

The temperature rise attributed to companies based in North America is on pace to be 2.9°C – less than the 3°C rise among businesses in the developed Asia-Pacific region, but more than the 2.5°C in the developed markets areas of Europe, the Middle East and Africa, according to MSCI. The emerging markets areas it identified have higher associated temperature rises for businesses operating within them.

Effects of US regulatory change

The US lags much of the world in climate policy for financial services, but it has made strides over the past year across nine different agencies, according to a new Ceres report.

Since April 2021, those government divisions have taken a total of 230 actions around the financial risks linked to climate change, with the Securities and Exchange Commission leading the way, Ceres found.

The organization produced a similar report last year, scoring the agencies in various categories. It found that, compared with global peers, the US had much to improve on.

The SEC this year has made a series of proposals that would require public companies to disclose their greenhouse gas emissions, include Scope 3, as well as damp down on greenwashing by financial services companies.

Ceres evaluated agencies based on whether they have publicly affirmed that climate is a systemic risk, produced research, assessed risks for financially vulnerable communities, appointed senior staff focused on climate change, improved disclosure and included climate risk in supervision and regulation.

The group graded the Federal Reserve System (FED), the Federal Deposit Insurance Commission (FDIC), the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA), the SEC, the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB), Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) and US Department of the Treasury.

Those agencies are all part of the Treasury’s Financial Stability Oversight Committee, or FSOC.

The report found that all agencies have identified climate as a systemic risk and have progressed in identifying the data that are needed to evaluate risks.

“Despite the strides that federal financial regulators have made over the past 14 months, they still lag far behind some of their global counterparts and what the latest climate science demands are.

“This regulatory gap could adversely affect US companies and stifle their competitiveness in the global market,” Ceres noted.

“While it is encouraging to witness US regulators acknowledging and acting on the climate threat, they must move faster.”