An over-reliance on data, in terms of reporting on diversity within companies, could lead to companies to rest on their laurels, warned Gresham House’s director of sustainable investment Rebecca Craddock-Taylor in response to a discussion paper released by UK regulators outlining suggestions to improve diversity in financial services.

In early July, ESG Clarity reported there was a focus on data collection and monitoring within the discussion paper, which was put together by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) and the Bank of England (BoE).

See also: – The dos and don’ts of diversity data

The paper acknowledged that most groups collect data on gender but said they should also be collecting data on “any of the protected characteristics and nationality, educational attainment, age, disability, sexual orientation, family status, carer and parental status, employment status (full time, part-time, flexible working), for example.”

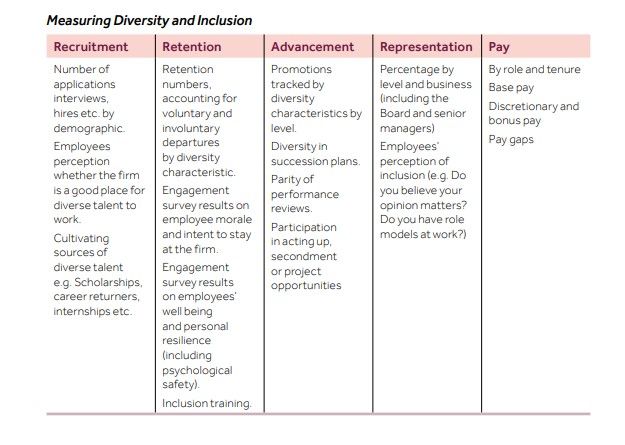

It suggested the following table as a guide to monitoring D&I:

Reporting in this way, the paper added, could become a regulatory requirement as it said: “We recognise that developing a new data collection would take time, and firms would need to build systems and collect the data from employees, where they do not already do so. Based on feedback on this DP, and the evidence received in the pilot data collection, including consultation with the UK data protection supervisory authority (the Information Commissioner’s Office), we will develop more detailed proposals on potential reporting requirements which we will consult on in due course.”

See also: – Industry waking up to importance of diversity data but not how to collect it

However, Craddock-Taylor highlighted the challenges of following these requirements with incomplete data, specifically that companies could use a lack of data as an excuse not to report.

“Introducing regulation in D&I monitoring and implementation should be welcomed so long as it is used to encourage action, as opposed to solely setting reporting requirements.

Data is extremely important in this area but it should not be a pre-requisite to action. There is a danger that regulating data reporting and monitoring could result in firms not taking action until they have the data to back up the changes they make. An over-reliance on data could create challenges if employees do not feel confident or secure enough to disclose their personal data. Hence resulting in companies and related stakeholders reaching conclusions using incomplete information.”

Little progress

She also suggested the discussions around D&I within financial services needs to move on, and noted, as did the regulator paper, that progress has been slow and focused primarily at the top level,

“The financial industry has had many years to improve D&I using voluntary approaches, such as the Hampton-Alexander Review and the Parker Review, but progress has been slow. Regulations could help to address the reality that a voluntary model has not had the traction the industry needs to ensure it better reflects the diverse society it serves.

The progress so far has mostly been focused on gender diversity at board level. However, change beyond boards has been even slower– there are just 16 female CEOs in the FTSE 350. To see real growth, we need D&I initiatives to be implemented across company structures, not purely weighted at the top level or at entry level (focusing only on internships or graduates).”

Craddock-Taylor suggested the conversation be moved to focus on how the financial industry can better serve clients with a diverse workforce, rather than providing evidence diverse companies outperform.

“Financial service firms should reflect the society it serves, and it should not require proof that a more diverse and inclusive workforce will create value. We have never asked for proof that the status quo works, so it is difficult to justify that we need to prove another way of operating is better or worse. The conversation needs to change from what D&I earns us, to how D&I helps us better serve our stakeholders,” she concluded.