The past five years have been seismic for energy markets and renewables, with widespread volatility due to geopolitical events ranging from the Covid pandemic to Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine.

According to the International Energy Agency, the slump in electricity demand during the pandemic was greater than at any time since the Great Depression of the 1930s. This was followed by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 which led to an unprecedented spike in electricity prices as Russia cut supplies to Europe by 80 billion cubic metres. This, combined with the European Union’s commitment to phase out energy imports from Russia, pushed up prices dramatically.

However, suggesting that every cloud has a silver lining, the crises saw the consumption of renewable energy increase, helping in part to fill the gap between demand and supply.

Wind turbines and renewable costs

Yet, while it has been a sunnier picture for renewables overall, the picture is more nuanced for some areas. The supply chain constraints caused by Covid, followed by a long period of super-inflation, meant wind turbine manufacturers were loss-making on fixed contracts that took around two years to wash through. This has meant a rebalancing up of wind turbine prices (solar prices continue to slide).

The spike in interest rates, and subsequent rising cost of debt has hit all capital heavy industries, including renewables. Despite this, on a LCOE (Levelised Cost of Energy) basis, wind and solar are still extremely competitive versus natural gas.

The good news is we have also seen upward pricing in power purchase agreements (PPAs) from blue-chip companies – i.e. the price large blue-chip companies are willing to pay for green electrons straight from the renewable operator has increased. This is positive for renewable generators who can secure long-term PPAs from corporates as it improves their returns.

Strike prices for competitive new wind and solar projects have increased to reflect higher costs while still remaining competitive.

Offshore wind

When it comes to installed offshore wind capacity, the UK is a leader (other areas include the US and Taiwan) and acts as a bellwether for this industry.

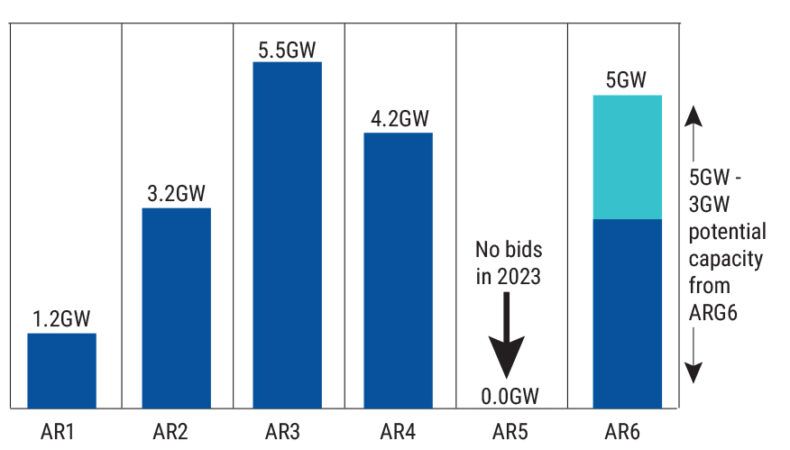

Much was made of the fact that here in the UK, in the 2023 Contracts for Difference (CfD) auction, AR5, there were no bids from developers to build new offshore windfarms. The industry had warned the price cap was too low to be economic, but the regulator failed to change it.

However, following the AR5 auction, the previous government increased the maximum price for offshore wind projects for the subsequent CfD auction, AR6, to account for the impact of high inflation, debt costs and supply chain difficulties. The result of AR6, announced in September 2024, saw 4.9 gigawatts (GW) of new offshore wind, and 3.3 GW of solar.

Globally, there has been a clear increase in regulatory support for renewables, particularly in the EU, and the US. While the US is not necessarily immune to a reversal of the flagship Inflation Reduction Act – it remains to be seen what will happen once Trump again takes office in January – the outlook globally is brighter.

The outlook over the coming decade or more is strong for renewable wind – particularly onshore which represents roughly 80% of the market by volume but is less talked about, with most people instead favouring high-profile offshore projects. We see the mispricing of big offshore projects working through as developers become more disciplined and factor in higher capital costs and costs of debt.

Blowing in the wind

The quest to lower costs compared to other technologies by making ever larger turbines has been paused in Western turbine manufacturers. The largest turbines in the pipeline now are the 15 to 18-megawatt turbines, as manufacturers run with the current models, and therefore avoid further congestion in the supply chain.

The biggest barriers to adoption are grid connections (the grid needs upgrading); planning permissions; and debt costs which need to normalise.

One threat to keep an eye on is that China is apparently entering some emerging markets for wind. However, Chinese wind turbine manufacturers may struggle to gain meaningful market share in developed markets as price is not the main reason for turbine choice. Supply chain, logistics and long-term service contracts are critical for developers and financiers of wind projects in developed markets and here the incumbent western manufacturers have a significant advantage.

The outlook on long-term power prices is always hard to predict but there is a strong argument to assume a higher for longer situation, as a result of increased demand from the electrification of transport, industry and heat.

We think the doom-laden commentary on renewables is misplaced. We see the structural shift away from fossil fuels to lower carbon energy sources as continuing and likely to further strengthen over the next decade.