‘ESG’ as a label has faced many obstacles in the past few years within the investment community, but as a way of investing it is clear it is here to stay.

As ESG Clarity rebrands to PA Future, we thought it would be an opportune time to take a look at how the term got off the ground, where it reached its pinnacle of popularity and where it is today.

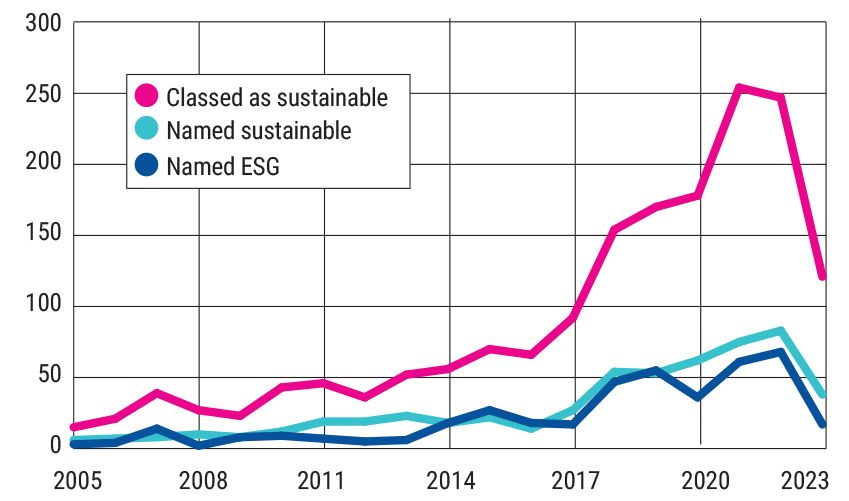

Using Morningstar Direct data on open-end funds and ETFs available to buy in the UK, and classed by Morningstar as sustainable, we have mapped the launch of funds with ESG in the name.

The picture of ESG-named funds between the mid-noughties and around 2015 is quite patchy due to a lot of rebadging, according to Julia Dreblow, founding director of SRI Services and the Fund EcoMarket. Morningstar also noted their fund data had not accounted for rebadging. For example, the passively managed State Street World ESG Index Equity fund (SSGA) first appeared in 2005, although under a different guise – SsgA World SRI Index Equity fund. It was renamed in 2015.

Dreblow said this is a typical case where a noughties fund became ESG just as the buzz around the term was building up. She explained ESG began to crop up more in the investment lexicon and in fund strategies in roughly 2010 before making its way into fund names a decade ago.

Dreblow said ESG evolved from SEE which stood for social, ethical and environmental. “But the institutional market hated the word ethical,” she said.

Dreblow noted a number of large corporate collapses led to world-leading governance standards in the UK and eventually “governance” finding its home in ESG.

Peak ESG

2019 was a bumper year for ESG-named fund launches with 55 in total, according to Morningstar Direct data. But the peak was in 2022 with 68 launches. Last year saw a sheer drop down to 17 funds launched with ESG in the name.

With around 30% of EU sustainable funds being passive, the fund type was overrepresented in the list of ESG-named funds, making up 64%.

Dreblow said the reason most funds with ESG in the name were passive was probably due to ESG and passives being a good fit, with both being “light touch” on sustainability.

“The chances are [the passives] are buying a data feed from someone like MSCI which enables them to integrate ESG risk,” she commented.

ESG vs sustainable

Over the past 19 years, 422 funds sporting the ESG name were launched, Morningstar Direct data shows. In contrast, funds with sustainable or sustainability in the name were one third more prevalent with 560 funds emerging in the same period, including 38 last year. Looking at the earliest inception dates, one of the first ones we spotted was the M&G Global Sustain Paris Aligned fund, launched in 1967. At that point it was the M&G Global Select fund and was renamed and aligned with the Paris Agreement climate change goals in 2021 – rebadging has by no means been limited to ESG.

According to Morningstar Direct data from 2014 to 2023, the largest spike in launches of funds Morningstar classed as sustainable occurred in 2021, with 254 appearing that year. However, for funds with sustainable in the name – as with those called ESG – 2022 was the big year when 83 were launched.

Fund launches

New funds called and classed as sustainable dropped significantly last year, but not in quite as steep a fashion as those with ESG in the name, which fell by 75%.

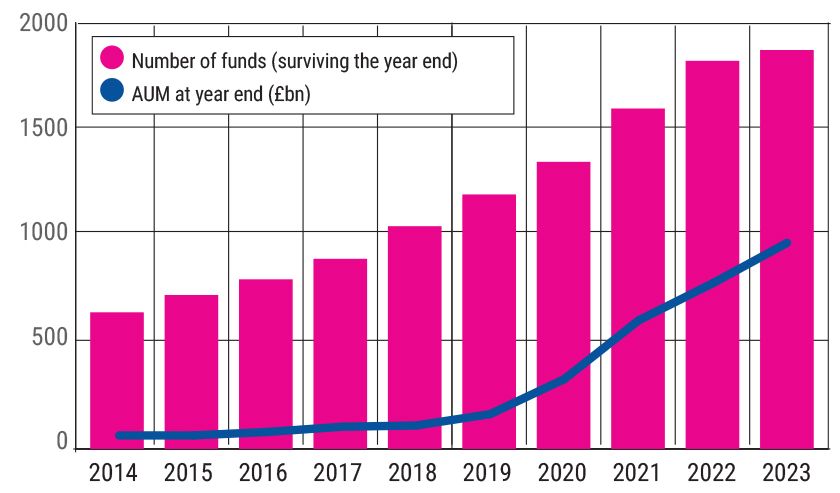

Meanwhile, Morningstar Direct data indicates no drop in the total number of sustainable funds or the total assets under management in such funds with both continuing to rise. AUM for sustainable funds available to buy in the UK reached £956bn by the end of 2023.

Good intentions

‘Sustainable’ and ‘ESG’ as terms certainly have suffered recently. One of the issues with ESG, Dreblow noted, was a gap between how authentically sustainably a product is compared to how it has been marketed – resulting in greenwashing allegations. Further, in the US the political backlash against ESG has gone so far as to make it a “toxic term”, she said.

You only need to look at the FCA’s Sustainability Disclosure Requirements (SDR) in the UK and the International Sustainability Standards Board globally to see sustainable is the term to have won the day over ESG when it comes to regulation. Dreblow welcomed this shift and said the sustainable name clearly indicates more intentionality around doing good and minimising harm.

But the lexicon remains far from clear cut for those subject to the regulations as investors themselves continue to be wary of both the ESG and the sustainable badge.

On pause

Looking ahead, Dreblow does not see sustainable funds, or sustainability as a brand, dropping off a cliff, rather she sees it as on pause while regulatory changes are afoot and a way to avoid unnecessary regulatory risk.

“A lot of people are talking about the slowdown and [sustainable funds] stopping launching. But they’ve rightly had to press pause because it could be a regulatory risk… launching something at a time when you know new rules are coming.

“It’s just business and it just doesn’t make sense to launch something into a market if we don’t know what the market is going to look like in six months’ time.

“I think once people get their heads around what SDR means and they have finished all the rebranding and done all the new literature, which is going to be quite a headache… We’ll start seeing a lot more funds being launched again.”

Number of funds classed as sustainable and total AUM