How much progress have you seen with carbon pricing over the past 12 months?

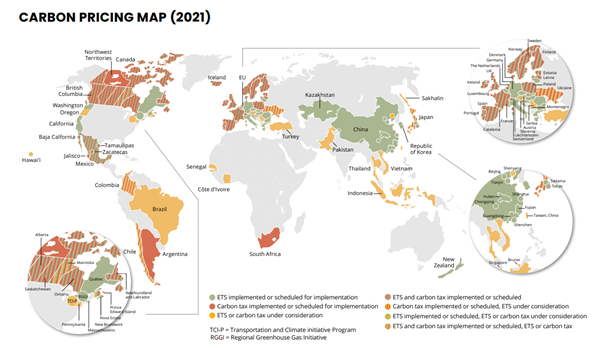

Governments around the world are starting to price carbon by imposing mandatory carbon markets on energy-intensive sectors. This is particularly notable in the power sector and manufacturing such as steel, cement, plastic and petrochemical industries. According to the World Bank, the number of carbon pricing schemes around the globe increased from 19 in 2010 to 64 by the end of 2021. There is no update available for 2022 yet.

There is a good map in this report from the World Bank that provides an overview of global coverage of carbon pricing. A lot needs to be done still!

What is the main barrier holding up effective carbon markets?

Globally, the main barrier is the fact many governments are not willing to implement carbon markets yet. Strong governments [need to] set up carbon markets that provide companies with the right price incentives to lower their emissions.

Voluntary carbon markets still need global high-quality standards to be enforced. Recent development like the adoption of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement – which sets out rules on how countries can reduce their emissions using international carbon markets – or the establishment of core carbon principles from the Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets, are first steps.

What is the price of carbon now and what should it be?

That’s a difficult question to answer! So many factors are at play. In general, global emissions have to peak before 2025, be halved by 2030 and reach net zero around 2050 to keep global warming within the goals of the Paris Climate Agreement.

If governments aim to reach emissions reductions by market forces, it requires a carbon price of €80-€100 per ton of CO2 now, rising to €140-€160 per ton in 2030. Towards 2050 you also need technologies such as direct air capture in order to reach net zero, which are likely going to cost more than €300 per ton of carbon in real terms.

But if governments rely more on rule-based regulation – such as banning the driving of cars with internal combustion engines or generating power with oil and coal – instead of market prices, the overall price level can be a bit lower. In developing countries, the price level can be slightly lower than in developed countries as these countries provide cheaper opportunities to lower emissions.

Are carbon markets big enough to meet the needs of all the net-zero commitments being made?

Not at this stage. Carbon markets need to be broadened across countries and within countries they need to include more sectors (not only manufacturing and power sectors). Finally, the level of carbon prices needs to be in line with price trajectory of a net-zero pathway.

ESG Clarity also heard from an ING spokesperson about the group’s carbon footprint and its use of offsetting.

What type of offsetting does ING use for operations and what kind will it use for its investment portfolio?

We monitor and manage our environmental impact closely and believe in being transparent about the climate impact of our operations. We invest in operational efficiency solutions and integrate sustainability into our procurement processes.

Since starting our environmental programme in 2014 we’ve reduced our total estimated operational carbon footprint by 79.8%. During 2021 we continued to compensate for the remaining emissions – caused by business travel and the use of non-renewable energy such as natural gas – through purchasing voluntary carbon units. These are provided by Redd+ and you can read more details about them in the information on environmental programme. We’ve been offsetting our remaining emissions since 2007 and are now looking to decrease our usage of offsets as we further reduce our footprint.

We don’t use offsets to compensate for the CO2 emissions of our lending portfolio. We do steer our portfolio towards the low-carbon technology needed to reach net-zero goals – like hydrogen, carbon capture and energy storage – and away from high-carbon technology. We call this our Terra approach. We aim for net zero by 2050 in order to keep global warming to no more than 1.5°C.

In terms of reducing absolute emissions, how is ING working to decrease exposure to fossil fuels? Banking on Climate Chaos reported ING provided $10.6bn in fossil fuel financing in 2021, including $939m of financing for the top fossil fuel expanders.

ING committed to the climate goals of the Paris Agreement in 2018. In August last year, we committed to the most ambitious climate goal of the accord of no more than a 1.5°C temperature increase – “net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050”. We are also bringing our loans to the oil and gas sector in line with the goals of the Paris Climate Agreement.

By 2025, our upstream oil and gas portfolio will be 12% smaller compared to 2019 and we are on track to reduce it by more than 50% by 2040. Our funding of coal-fired power plants will be close to zero by the end of 2025. In addition, we announced in March that we will no longer finance new upstream oil and gas projects.

A transition period is needed to move from fossil fuels to renewable energy – including in relation to security of energy supply and its affordability – and we’d like to support our customers and the economy in this transition. We remain committed to our 1.5°C climate commitment and the exposure reduction targets set in our 2021 climate report.