There is a job to do in rebuilding trust in investors’ ability to report on sustainability credentials, especially as the asset management industry has recently been hit by some high-profile greenwashing scandals.

Asset managers such as DWS, Goldman Sachs, and BNY Mellon have been subject to criticism around greenwashing and senior industry figures have added impetus to the debate with controversial remarks criticising the effectiveness of ESG as a risk framework. Regulators in Europe and the US are starting to pay closer attention…and hand out fines.

Against this backdrop, investors must now meet tougher standards if they want to market a fund as a sustainable product and are acutely aware of the significant reputational risk if they misrepresent ESG credentials. With the introduction of enforceable regulation like the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) in Europe and with the recommendations on ESG fund regulation from the SEC in the US, scope for investors being caught out for greenwashing will only increase.

SFDR could revolutionise sustainability reporting – and, in turn, rescope the data that companies track to measure their ESG performance. But it is by no means a silver bullet. While regulatory moves and corporate disclosure regimes are crucial, they are only useful if the data is reliable and investors and companies can easily compare and analyse the information provided.

SFDR data not available

Not every piece of relevant data for full SFDR reporting is available at scale yet, and it will be at least another five to 10 years before this changes. Making the right data available at scale requires overcoming two main obstacles.

First, there is the issue of the questionable reliability of reported data. This can occur, for example, because reported company data is non-standardised, contains mistakes, or does not cover 100% of company operations.

The second issue is incomplete data coverage of metrics and industry sectors. This occurs because of partial or non-existent reporting.

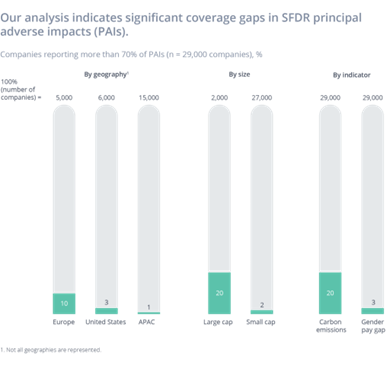

The graph below illustrates SFDR Principal Adverse Impacts (PAIs) coverage gaps by geography, size and selected indicators based on our data science-enabled analysis of 29,000 companies.

PAI indicators are a set of specific ESG metrics mandated by the European Union as part of the SFDR. As a reminder, SFDR imposes granular sustainability disclosure obligations for asset managers and other financial market participants.

Globally, only 3% of companies analysed report more than 70% of the 14 mandatory PAIs for corporate investments. Europe leads the way with 10% of firms meeting this coverage threshold, while just 3% of US firms and 1% of APAC firms reported the same. One in five large-cap firms met the threshold, but just one in 50 small-cap firms do.

Coverage gaps by geography, size, and indicator

Asset managers can’t wait

In sustainable investments specifically, while taxonomies and frameworks are certainly important, it is through data, science and technology that investors can improve their analysis of companies, globally and in a scalable way. Technology and artificial intelligence tools can help assess the reliability of the reported data, fill in the gaps in ESG datasets, and aggregate and automatically generate the information required to meet the challenges of SFDR. Asset managers are starting to recognise this and are utilising big data and AI to facilitate efficient and accurate reporting on PAI indicators.

Waiting for perfection in order to change behaviours is incongruent with the urgent and ambitious pledges that have been made over the past 10 years, reiterated even more recently at global conferences, such as COP26 and likely again at COP27.

The investment industry will need to act with speed, using the best technologies and tools available, to play their part in advancing us towards a more sustainable world.