Recent critiques of environmental, social and governance investing tend to seek emotive rather than rational appeal, with critics using words like “delusional,” “incoherent,” “scam,” “cabal” or “idiots.” Such rhetoric may fuel clickbait, but it distracts from valuable and informed discussion on how ESG can evolve. In navigating anti-ESG media, it’s valuable to separate well-founded criticisms from misguided cynicisms.

Well-founded critiques

Greenwashing is likely occurring in the ESG market. Recent regulatory probes into some large asset managers show that ESG greenwashing concerns are merited. With money rushing into the space, it’s not surprising to find a few nefarious actors looking to make a quick buck. Firms that mislead investors will lose their trust and thus their assets.

ESG ratings lack agreement. Critics point to the lack of correlation across ratings organizations and suggest this undermines ESG investing, writ large. To be sure, ESG is a subjective space. Still, how one weighs decreasing emissions versus community impacts is not unlike considering the implications of taking increasing debt to expand capacity. Life is filled with trade-offs.

Misguided cynicism

ESG practitioners overlook how ESG affects firm value. Cynics suggest ESG investors don’t care about returns and fail to substantiate how ESG relates to financial performance or risk. This ignores the preponderance of work done by nongovernmental organizations, academics and practitioners, which links ESG issues to the fundamental inputs (cash flows, growth and discount rate) of valuation.

A more moderate, efficient market-based claim argues that if ESG has any riskless financial benefit, then it will quickly be valued. The capital asset pricing model put forth a stock’s expected return depends on its risk. The Fama-French five-factor model further built upon the CAPM.

According to the five-factor model, profitability helps explain stock outperformance. Since the model was published in 2013, profitability has been the best performer of all additional explanatory factors (size, value, profitability and investment) to market risk. Arguing that greater profitability is riskier is far-fetched, and nine years is enough time for an efficient market to arbitrage non-risk-related excess returns.

Source: Bloomberg

Maybe persistent excess returns can be found without excess risk. What’s more, a New York University meta-analysis found 58% of studies confirmed a positive relationship between ESG and financial performance. The analysis further showed, studies with a long-term focus were 76% more likely to establish a positive or neutral relationship between ESG and financial performance than studies with a short-term focus.

ESG practitioners pretend trade-offs between E, S and G don’t exist. Nowhere have we seen ESG practitioners suggest such trade-offs do not exist. To again use a financial analogy, analysts don’t only look at profit margins to determine investment attractiveness, we look at myriad metrics, including how a company intends to balance maintaining margins while growing its business. ESG is a piece of the mosaic that gives us a better view of the company.

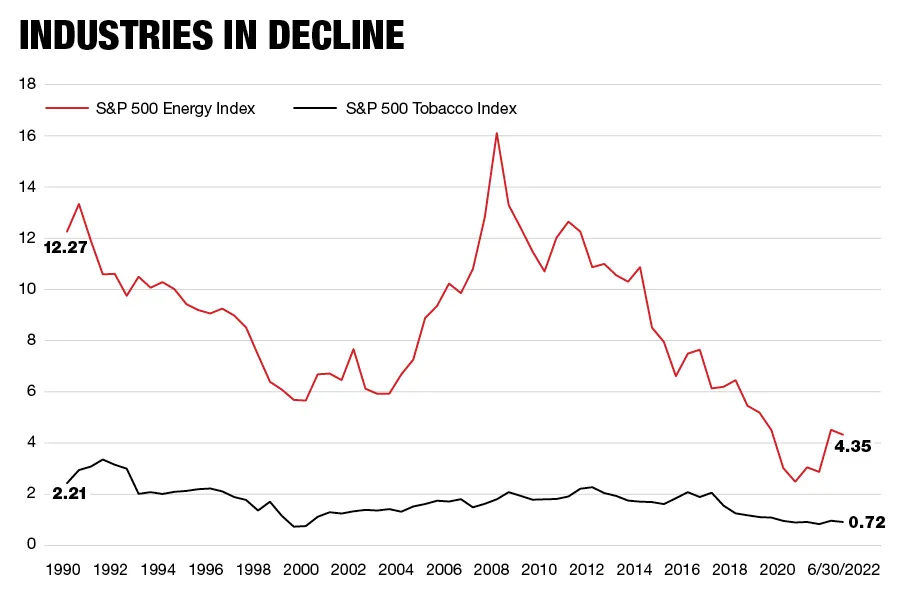

Being good for society can’t be good for investors. Adam Smith wrote, “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own self-interest.” It’s also not out of spite by which we get our dinner. Many have countered “doing well by doing good” claims with anecdotes of superior returns from the tobacco industry and the energy sector. Sure, tobacco staged a comeback after lawsuits in the 1990s, and energy has recovered since Covid-19 lockdowns caused negative oil prices. A review of industry weights in the S&P 500 dating back to 1990 shows that tobacco and energy are a fraction of their historic size. So is it best for business to turn its back on society’s values?

Source: Refinitiv, Bloomberg

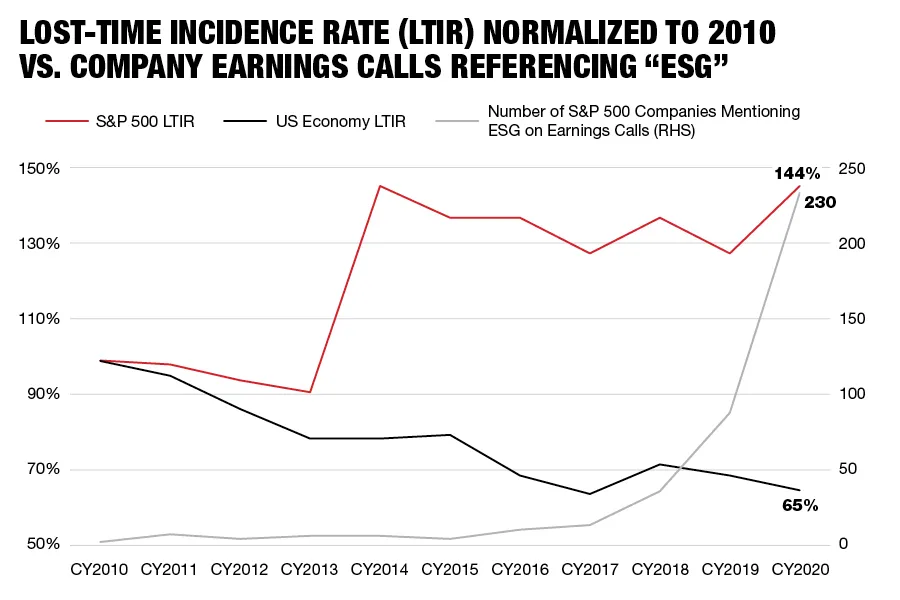

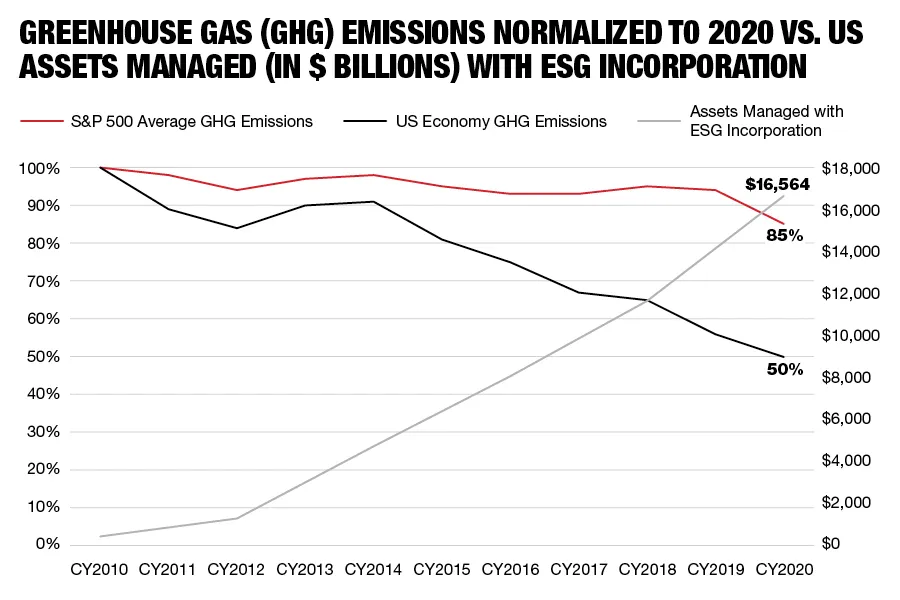

ESG has no positive impact. Substantiating that ESG investing causes positive impacts at a societal level is tough. But consider this: From 2010 to 2020, assets under ESG management have exploded, with mentions of “ESG” on earnings calls growing exponentially. During this same period, average greenhouse gas emissions (Scope 1 and 2) for the current S&P 500 cohort have fallen by 50%, versus a 15% decrease in the wider US economy. It’s also striking that lost-time incidence at these companies has dropped 35%, while it’s increased 44% in the wider US economy.

Source: Refinitiv, Bloomberg, US SIF

Markets can’t be separated from society. If society wants cleaner, more diverse and more ethical companies, then people are fully within their rights to leverage their investments. Critiques of ESG are also part of a functioning market; they will make the industry more reflective and encourage improvement. Markets work through trial and error; the evolution of ESG is no different.

Levi Zurbrugg is a senior analyst and portfolio manager at Saturna Capital.

This column first appeared in InvestmentNews.